Over the past week I’ve spent time in the well-deserved mecca of hiking – the far south region of Latin America known as Patagonia. Visiting both sides of the border – Los Glaciares National Park in Argentina and Torres del Paine in Chile – allowed a window into the significant contrast in trail quality and hiker behaviours within Argentina.

As with any trail that is both massively revered and has the trailhead directly accessible from your hotel doorstep, I knew Argentina’s Laguna de Los Tres trail has heavy foot traffic. What I did not foresee, was the blatant ignorance of hikers to cooperate in signposted ecological restoration efforts. The trampling of bushes. The wearing down of formerly untouched areas. Mass traffic creating massive clearings of new trail. Which all got me thinking – what leads people, specifically nature-focused individuals, to engage in these poor trail practices, and how can we employ design and behavioural nudge tactics to change this?

Side note: I’m no ecologist nor have much experience in the environmental sciences – but purely as a fun exercise let’s explore some behaviours as play.

Image: Mount Fitz Roy

Grasping the problem

To illustrate the scale of why this is worth discussion, Argentina’s Mount Fitz Roy, and it’s associated 24km trail ‘Laguna de Los Tres’, has won Trip Advisor’s “Best of the Best” rating, the highest possible honour where award winners are among the top 1% of listings on the platform. In more specialist terms, its entry on hiking app AllTrails has the most 5-star reviews I’ve witnessed of my 700km of hiking this year. Oh, and the mountain’s outline is the basis for the logo of the Patagonia clothing company. So a pretty big deal – metaphorical and otherwise.

Argentine Patagonia is one of the world’s premiere nature destinations and this trail can have literally hundreds of hikers per day during the summer season. In this particular trail system, there are many more people causing damage through foot traffic and metal-tipped pole usage than there are balancing environmental actions to correct it. With the growing tourist popularity of the region, new infrastructure projects abound and seemingly minimal checks and balances, its a high likelihood that this trail is ecologically unstable to continue in the future. This would affect tourism, local ecology and wildlife, and selfishly, our ability to enjoy the grandeur of nature that we so love.

So where does our problem really lie? Most of the trail is fairly flat and well-carved out in a single direction, which localises and limits the damage that can be afflicted. Like a cricket pitch during the Australian summer, theoretically one could cover the trail and re-route traffic to an alternate, giving the path respite and space for recovery. However, the bulk of our current problem occurs 10km into the hike at the point of final ascent – a hour long journey of steep grade, criss-crossing open pathways and where many signs of erosion, weathering and tired hiking occurs.

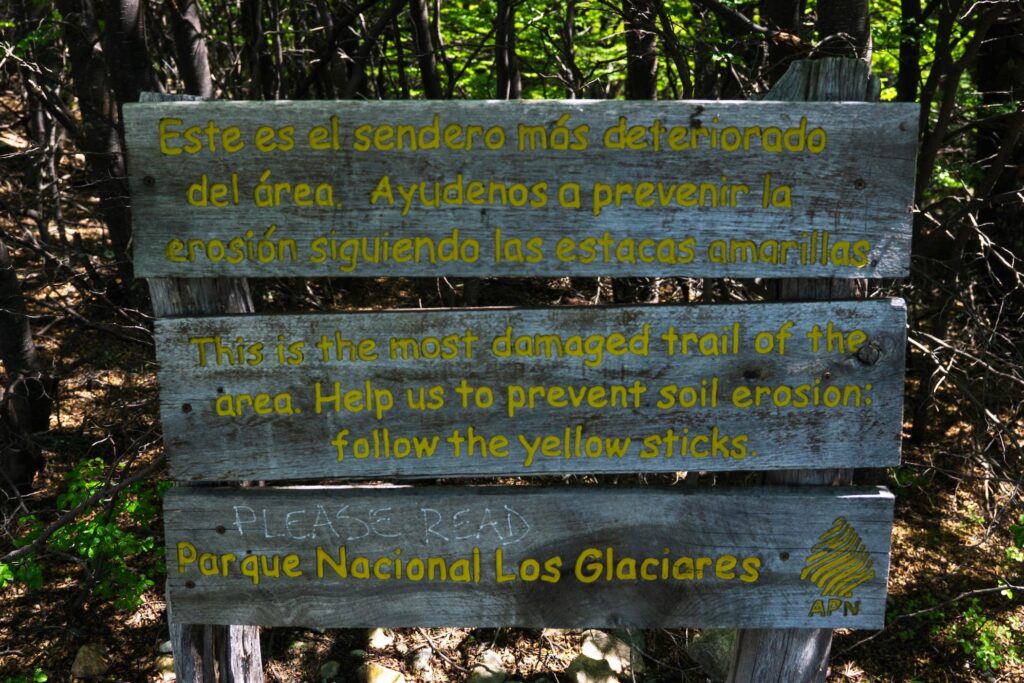

To combat this, the parks team have tried to craft many recuperation areas and a single-path zone by having somewhat clearly marked trail indicators, multi-lingual signage that informs the public of their efforts, and by placing “don’t walk here” markers in front of sensitive areas that need to heal.

Good first steps. But, being currently non-compliant, appear to be ultimately useless.

Image: soil erosion on the final ascent to of the Laguna de Los Tres hike

Image: multi-lingual signage before the final ascent unfortunately located in a low visibility area

Key factors in a declining trail

Let’s first tackle the obvious problem with the current setup.

- There’s no entrance fee or limiting visitor number to curb the amount of possible human traffic.

- With a lot of people, there’s not a lot of rules and no ranger enforcement.

- The “Don’t walk here signs” are dilapidated, which both makes them hard to read and may serve as an indicator to hikers that this project is no longer of importance and may have been abandoned.

- The instructions to the public are important for educational purposes, but are placed in a zone of darkness between trees where hikers will likely have their heads down watching the trail.

Image: comparison of signage deterioration. left: sign on Laguna de Los Tres trail. right: sign on another trail.

Aside from the obvious, there are the behavioural factors of hikers on a trail, which we can class into the categories of group dynamics, hiker fitness and desire.

Group Dynamics – given the vast popularity of this trail, group dynamics may be one of the most significant problems to solve. Day hiking is a super popular activity here, with groups of 10+ people being a constant. In these situations where a bunch of unacquainted tourists are brought together for one day to form a pack – the behavioural heuristics of Authority Bias and Social Proof and are especially evident. Hiring a reputable tour guide offloads our need to think. It invokes trust in this expert that what they say and do is gospel, so we’re essentially play a game follow the leader. If that leader is not heeding to signage, neither are we. Who are we to question the local guide! Similarly, even if we were highly ecologically minded and wanted to steer clear of these zones that our fellow group members were trampling, it can be hard to override our socially minded mentality that says “don’t rock the boat – follow the group and fit in”.

Hiker Fitness – being the final ascent of 11km in upwards trail, there are tired bodies everywhere. This tiredness is exasperated by the popularity and ease of access to the trail, allowing a much wider range of fitness levels be involved in the fun (good! but also bad). Unfortunately where trail maintenance is concerned, many will simply miss trail markings due to fatigue, and these tired hikers quickly turn into rogue agents looking for any shortcut to ease their suffering.

Desire – through this fatigue they create and contribute to desire paths – routes that haven’t been officially marked or created, but due to many people’s perception of a better route, are forged out unofficially. We’re also dealing with the desire of large-spending Patagonian hikers for unadulterated exploration. Being able to take any trail they wish to get away from the crowds and explore something seemingly unexplored. Further, such large groups on an out and back trail lead to competition for trail space, both in an overtaking and two-way traffic capacity. With a trail not wide enough to accomodate both, another desire and necessity for alternative trails arises.

Through the final hike upwards, the trails that hikers decide to take overlap heavily with the areas that are signed with a need to be recuperated.

Image: hikers snapped not following “keep off” signage, even when the signs are in good condition

Of course, we could fix this through deterrence – i.e. enforcing a daily cap on visitors, a park entry fee, or building infrastructure that would move traffic from affected areas. But what’s the fun in exploring that?

Strategies and tactics to help solve the problem

The first strategy involves better education through appeals to emotion. Appealing to visitor’s self-image as nature respecting adventurers, messaging should be clear and upfront at the trailhead about the delicacy of this environment and a need by all to protect it – especially you, who I know is a humble and dedicated explorer and protector of the natural world. Simple ground rules (literally) for visitors should be stated at the start of the trailhead and then restated through highly visible reminders thereafter. Signage later in the trail could work towards emotional resonation, acknowledging the hikers state of mind and redirect their thinking – for example: “we know this section is very fatiguing, so please stick to the marked trails at this critical point so you can continue exploring Patagonia uninjured”. For those that feel they are explorers, messaging could temper their desire by acknowledging the already remoteness of Patagonia, and appealing to the fact there are are minimal rules, that they need to be their own enforcers to keep the area in check.

Strategy two is codified trail and signage maintenance. Signage should be refreshed to show seriousness, and optimised for visibility and distinctiveness by utilising colour. The trail to be taken should be highly obvious and visible. Implicitly stated, red markings naturally have connotations of danger which works in recuperations favour. Roping off sections – a physical blocker and redirection tool, would greatly aid to place paths ‘off-limits’, while adding knotted rope or chain to difficult or steep climbs would signify them as the default option for fatigued climbers. Multiple trails should also be constructed, which would negate the chokepoints of two way traffic into manageable flowing pathways.

Strategy three, that which is the most fun and also likely the hardest to implement, is both the incentivisation of good behaviours and disincentivisation of the bad. One such incentivisation would be to create an optimal path that snakes through pre-determined viewpoints, rest stops and landmarks. Naming these points of interest would further their credibility as something to be explored and completed, further amplified if this whole section of trail is named and elevated in its status as a path of significance. A believer in the duality of everything, disincentivisation is also required for success. To counter the tour guides with bad habits of unconscious or entrenched routing, a park ranger should be placed in this section temporarily to act as the new authority. Their presence would enforce trail routes, re-establishing credibility that there is effort being spent on ecological restoration efforts, and using their platform and visibility to remind the tour guides that trail degradation on the most popular trail in Argentina is a risk to their economic viability as an operator.

It is my hope that this problem receives some attention in the coming years and that we can all continue to help save nature spaces, if nothing else but for our own selfish enjoyment of them.