In his book Superforecasting, Philip Tetlock notes that throughout history we’ve been awfully good at spouting predictions of the future, yet consistently fall short in measurement and taking stock of what holds up.

With South By South West about to kick off for another year, I thought this would be a perfect time to ruminate on the ideas from the past that still have legs. This is not a recount of tech that came to pass, rather, these are the ideas that still kick around in my head to this day.

To set the scene: it’s March 2022 in sunny southern Austin, TX — the first large in-person event after the pandemic. There’s music, film and art. Advertising, startups and space. Business people talking psychedelics. Psychedelic people talking business. If tech-bro utopia had a baby with Woodstock had a baby with wellness influencers, it wouldn’t even start to describe the breadth on offer. The theme was ‘The Metaverse’ (spoiler: this is the last mention of that).

In a new context of return to thriving office spaces and generative LLMs taking over everything — what remains prescient?

Image: it was an art exhibition, I swear.

Know Thyself(s) in an Identity Divide

TLDR: we must understand ourselves deeply to know how far we can be malleable in any direction and still be able to snap back.

A standout presentation that lives rent free in my mind is that of Jack Conte – CEO of creator-fuelling platform Patreon. To this day, his style of 800 slide rapid-presentation stays with me as the gold standard for entertainment x knowledge. In essence, the theme to his presentation was to be human — truly yourself — and accept no bullshit; a notion which can easily be lost at SXSW with its trends, branded experiences and buzzwords. He believes one person’s advice is only a single data point in a sea of any other better, or worse, advice. He questioned why we so often seek out the answers from one source, one person, one success story — a confirmation bias of popular opinion. These data points don’t have our life experiences; they aren’t us. Following that logic, their advice probably isn’t best suited for us. Jack’s story isn’t ours; his advice unlikely to be tailored to our goals and aspirations. So, whenever he would reach a logical segment conclusion, the thousand+ audience members were encouraged to scream “Fuck you, Jack!” in unison. Entertaining, right?

Different parts of ourselves want differing things. We make conscious decisions to show and hide certain parts of ourselves in a split second to gain tactical advantage, show empathy, develop relationships, build and destroy trust. Who we are around our families is different from our friends; our workplace self is different from our romantic self. We shouldn’t, nor can we, give all parts of ourself to all people. This natural personality split is normal to be a healthy, functioning human in everyday society.

However, the problem that Jack spoke to, as did a Salesforce panel and many others, was that of the acceleration of our fracturing digital identities — the multitude of accounts, aliases, and profiles that make up our online lives. Following the previous logic, I am not the same person on my Instagram, as my LinkedIn, as my website, as my musician alias. This is purposeful. The difference to the real world scenario is that all of these profiles and data can be linked back to me with one Google search. With proliferation of single-sign ons, where a singular identity starts to take shape and our digital identities begin to blur, parts of myself I’ve contextualised by design will be pulled and morphed into one another. This has consequences for free speech, for how our colleagues and friends and family can relate to us, for already fragile societal mental health.

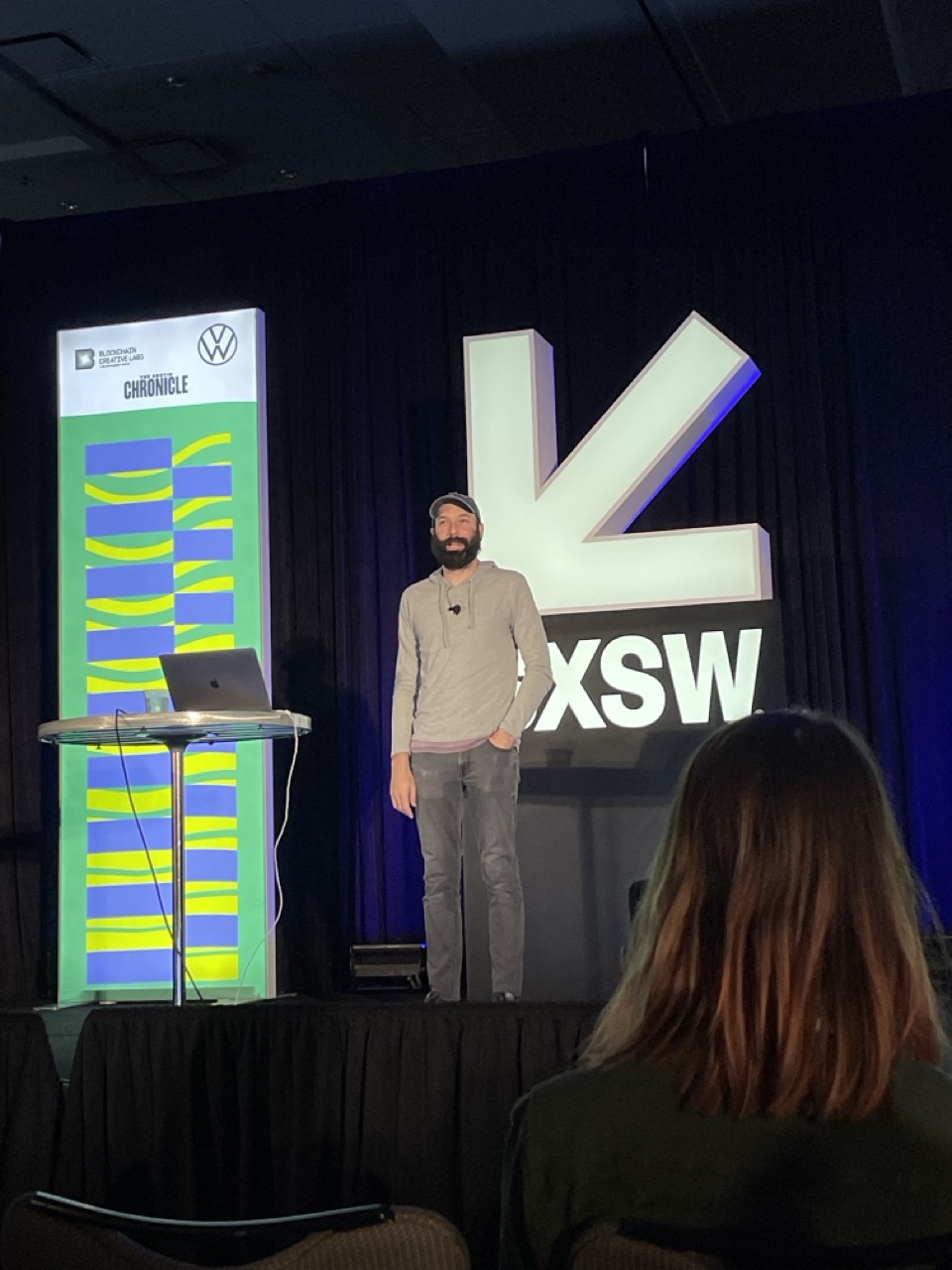

Image: Jack Conte standing peacefully before he asked us to flip him off

Without unconnected profiles and aliases, how should we act when we inevitably wind up as the watered down, singular brand of ‘ourselves’ all the time? How will this affect how we show up? How we choose to interact and build communities? How we dissent on opinion and voice our own divergent views?

There is no standard or playbook on how we can import just the right parts of ourselves into our digital identities destined for work, learning and play. These are not easy questions.

Jack asked us to more often look within for the answers that will suit our needs, as messy, chaotic and un-process-like as we know that will be. In 21 Lessons for the 21st Century, Yuval Noah Harari discusses that one of the greatest threats to ourselves in this lifetime is simply not knowing who we are and what we want, for if we do not know, advanced algorithms and attention-farming technologies will dictate our lives and choices for us.

Two years on, with the current climate in heavy utilisation of generative AI, it’s not unfathomable that you could abandon your own thoughts and desires in favour of becoming a cyborg and experiencing the world through a generative lens.

“… know your operating system better. To know what you are, and what you want from life. This is, of course, the oldest advice in the book: know thyself. For thousands of years philosophers and prophets have urged people to know themselves. But this advice was never more urgent than in the twenty-first century, because unlike in the days of Laozi or Socrates, now you have serious competition. Coca-Cola, Amazon, Baidu and the government are all racing to hack you. Not your smartphone, not your computer, and not your bank account– they are in a race to hack you and your organic operating system. You might have heard that we are living in the era of hacking computers, but that’s hardly half the truth. In fact, we are living in the era of hacking humans.”

– Yuval Noah Harari

We feed these models information about ourselves, in the form of bios and TOV and custom instructions and formatted outputs, so that it can return information in a format as if it were us. Good tools used in the right context? Totally. Yet very soon it will become harder and harder to untangle the organic thoughts and feelings of the person that you are, from the synthetic layering of AI which tells you how you should talk and behave. Though these outputs are ‘easy’, they certainly are not you.

Here we reach a tipping point — imagine our multitude of online identities have been watered down and key-holed into a singular version of ourselves, that a generalised AI can further morph and dilute away from who we currently are into some synthetic version of ourselves. It’s what we asked it to do, but is it what we want?

Food for thought.

Designing for stress and crisis is better for everyone

TLDR: solving problems for niche needs and states of cognition often has disproportionate impacts.

In my work as a UX/CX Strategist, I’ve researched and crafted plenty of end-to-end customer journeys that outline the human emotions and activities at each stage of the purchase and usage cycle.

Too often, I’ve considered these to be the gold standard, reliable source of truth. But let’s be honest — this isn’t how we as humans attack the world. We’re not logical, IF-THIS-THEN-THAT type creatures. Emotions, ego, psychological desires, cognitive bias drive most of our decision making. We couldn’t survive a single day as wholly rational beings even if we were paid six times our salary to do so. Behavioural sciences have proved this — it just isn’t in our nature.

With this emotions-as-a-driver lens, Katie Swindler, author of Life and Death Design, gave an enthralling presentation in how we as humans act in times of stress, and how we can better design for people in times of crisis. The core idea here is that during these moments when we’re in even less control of ourselves than normal, our lower levels of biology take over how we interact with the world. For example, how does the experience we’re designing cater for someone who has just been in a car crash, whose startle reflex means that their large extremities are now moving faster, but their fingers are moving much slower? Whose body is flooded with cortisol and they’re not thinking clearly but relying on intuition to navigate decisions?

Image: Inclusive UX Research Panel featuring speakers from Airbnb, Cisco, Adobe, Uber.

Let me call out the obvious: most of us aren’t designing experiences to be used in high-stress environments.

However, more nuanced, latent stressors are all around us — from general workplace stresses, to financial and cost-of-living pressures; death and mourning to self-inflicted nihilistic life crisis; emotional glazing from a newly broken relationship, family incidents, general situational disappointment. All of these small and large moments in our lives contribute to the level that we can show up and be in control of how we act.

I like to call these low-cognition states: our environment and context is bringing down our overall ability to exist in the moment.

For many of us working on non-trauma defined audiences, our optimised, best in class designs aren’t catering to the low-cognition reality of people using our experience — and it’s foolish to think that pleasant design and fun interactions are going to pull them out of their world. Much of the time we’re asking for too much.

So how do we fix this?

I admit, it is much harder to upend the accepted frameworks and artefacts that we use to build empathy and inform design choices in favour of something known — something less black and white and a process with more grey. I know, it’s often my job to distil a grey into a form that is very black and white.

The good news is that spending time solving problems for niche needs often has disproportionate impacts.

Firstly, we need to bring real environments, real people, into the design process. I get this point has been hammered to death. But we’re still not learning, because we’re still getting it wrong. This simple step in the process was noted as a common, repeated failure across many of the design discussions at SXSW. From AirBnB and Uber to Google and IBM, companies are coming to the conclusion that the products they’ve created don’t meet the needs of the population.

Fast-forward two years, and we now have more sophisticated customer-listening technologies than ever, and they’re accelerating at an exponential pace (both fforward.ai and syncly.app were on the front page of ProductHunt last month). Using these tools is efficient, convenient and ten-fold easier to get stakeholder buy-in. But if the conversations from these behemoth companies are anything to go off, we’re still failing our users because we still believe we know better. We’re aggregating a bunch of data to stitch together an average view of a human.

Average models don’t work. To illustrate this point, look to the US Air Force during the 1950s. Lieutenant Gilbert S. Daniels, a researcher and a Harvard graduate, undertook a study to measure over 4,000 pilots on 140 dimensions of size in order to create the perfect cockpit for the average pilot. What did Lieut Daniels’ find? Out of the 4,063 pilots, not a single one fit within the average range on all 10 of the relevant dimensions for cockpit design. We have to be more focused.

We must go wider with research selection criteria — identifying more distinct niches of people who would struggle to use the experiences we design, and understand their various states of usage better.

Inclusive Research has a bunch of good articles as a starting point.

Second, I believe we should be designing for stress and inability as a first point of call. Just as we’ve evolved to developing unique usage patterns for mobile vs desktop, we should work from the ground up prioritising design for low-cognition states. A better experience for people in a crisis, people with stress, anyone with impairment, is usually a more intuitive, clean, delightful experience for everybody else. By including a few peak-experiences, we can add in the elevatory branded sparkle without complexifying the whole experience.

Designing experiences for low-cognition states will result in better outcomes for all.

And quick tip: if you’re designing digital experiences, providing a greater margin for user error can safeguard against many stress-based decisions/non-decision (button sizing, undo/back controls, confirmations, no closed doors).

We don’t have to join in on the bullshit

Rounding out the ideas is something more of a moral conundrum. It’s this idea that there’s enough junk in the world — we must produce things of substance.

Rohit Bhargava’s ‘Non-Obvious’ presentation laid bare that we’re surrounded by dodgy practices. ‘No added colours of preservatives’ in your cereal is a classic. Deep down, you know there is. The problem is, we as marketers are the worst offenders. If we’re given an inch of a potential claim to use in market, we often take a mile and milk it for all it’s worth. But we play a role in our societies. We have a part to blame in misinformation, in driving opinions apart, in manipulating peoples patterns of thoughts.

Jump to today, and there’s serious ethical questions facing each and every one of us in how much we should contribute to the noise. Should we adding to the clutter of the web by generating all our content using AI? Should we be using Sora, Dall-E and other imaging generation tools to shortcut speed to market and cut artists out of the process? If we don’t, will our brand fall behind and leave our business in the dirt?

Image: found my twin during a 3am burrito stop. Wholly unrelated to this article.

Jeff Bezos once said that most decisions are two way doors; if you choose one, you can always come back and try the other. It’s an active choice not to pull that trigger, but we don’t have to let it be the death of us.

This idea really hit home for me personally. I’ve often been prompted to more actively utilise social networking tools. Until now I have refused, not wanting to add to the bullshit. Jack Conte’s talk put into words this underlying feeling I’ve always had – that when we hit record, or post, we’re living as a brand; acting more as polished, witty, accomplished companies than the humans that we actually are. And that makes him (and me) feel alone. It feels like living in a world lacking substance. To connect with each other and to have the conversations worth having, we need to feel the human in it all.

So to end, let’s work to know ourselves and our story more deeply.

Let’s work to understand the people we create for and the emotions within them more deeply.

And let’s spend more time putting out signals that we’re real and true and human. Let our writing be a record of our time alive.

Cheers to that. Here’s to more years of SouthBy.

PS. Absolutely legendary shoutout to Dan Monheit for letting me join in on the 2022 trip. Best boss ever.